R. Harold Hollis

Unless compassion is translated into action, it is powerless.

Thursday, May 4, 2023

Stanley Barnes painting titled "The Thinker"

Tuesday, June 28, 2022

Indigenous woodenware

The bowl to end all bowls. Hand hewn, I'm assuming from Mexico and also assuming from a large Mesquite tree. Early 20th century, or even late 19th century. Estate sale find, in Albuquerque.

This piece could be from the Tarahumara Indians (Raramuri in the tribe's indigenous language) in the state of Chihuahua, northern Mexico.

Monday, June 27, 2022

Friday, June 24, 2022

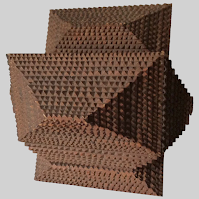

An Ode to Tramp Art and Texas Germans

In 2012 I sent to auction a collection I had built over 30 years. Texas-made furniture and stoneware, as well as paintings, quilts, and folk art. Several pieces of tramp art were part of the collection. I did a lot of buying and selling over those 30 years. My favorite tramp box was the one shown here, a cigar box piece featuring the chip or notch carving this folk art form is known by. The leather hinges worn out, crusty cocoa-colored paint, and a broadside photo image of the Skull Creek Schuetzen Verein in Shelby TX were the prominent attraction of this piece when it reached my hands in a trade in the early 1990s, all testament to its artfulness, age, history.

|

| Another tramp piece, a wall box |

The German enclaves around Texas were known for their gun & rifle clubs—the German schuetzen verein meaning shooting club in English. Their were several in and around Houston, and my German ancestors were members.

Growing up we went to the one in the area of Cypress Texas known as the Tin Hall, officially the Cypress Gun & Rife Club. I can’t remember who, but someone told me awhile back that the Tin Hall was a meeting place for the Ku Klux Clan. If true, this tarnishes somewhat my fond memories of gatherings there—barbecues in true Texas German fashion, the dance floor upstairs, worn smooth and made better with dance floor wax powder, and the old time guitar and fiddle bands that played the songs of the really good era of country music. As a kid I learned to dance the Little Brown Jug, Put Your Little Foot, and Ten Pretty Girls with my Aunt Edna Rustenbach Fuchs. German enough for you? I think there was a little Polish in her bloodline as well.

|

| Cypress Gun & Rife Club--the Tin Hall, 1888 |

History has it that Will Fuchs (born Wilhelm Friederich, 1869-1930), the man I would have known as Great Grandpa, though he was actually my great-great uncle, died while serving as an officer of the peace at an event held at the Spring Branch Gun & Rifle Club (Schuezten Verein) in 1930. A life-long Missouri Synod Lutheran in the tradition of his family, he was denied burial in one of the five gravesites he owned in the Trinity Lutheran Cemetery in downtown Houston because he died in a setting where alcohol was being served. Tough-minded Lutherans! The last home I owned in Houston, located at the intersection of Sandman and Rose in an old German neighborhood known as the West End, was built by Will around 1900. Will had to be buried elsewhere, of course, so his remains lie in St. Peter’s Cemetery, located in Spring Branch. And a little more history.

Spring Branch began as a religious German farmer settlement in the 1830s and became a part of the city of Houston in the 1940s-50s. In 1848, St. Peter's United (Lutheran) Church was established there.

It is the resting place not only of Will and his wife, Bertha Maria Rinkel Fuchs, but also of my grandmother, Lizzie (Elisa Christine, 1897-1983), along with her husband Frank Frederich (1897-1941), the son of Will and Bertha.

All that from a tramp art box!

Sunday, November 21, 2021

My love for American stoneware

Impossible to say which of all the antiques and collectibles that have passed through my hands and spent time in my dwellings over decades is my favorite. I love them all. Going back almost 50 years when early Americana captured my fancy, I was enamored of pieces that had escaped stripping and refinishing. For many things, like furniture, boxes, and splint baskets, that meant they were paint decorated. Swoon. From the beginning I have loved what are called by various names—Early American, Americana, Primitive, American Country. Collections have come and gone, and now living in New Mexico for these many years, my interests have centered around American Indian and New Mexico Hispanic work. Yet, there is a lingering of my collecting past—American stoneware.

And much more that lingers, including quilts, splint baskets of Anglo American production, and more more more. All of these pieces of stoneware pictured here have lived out in an open shed in my “back 40” for the last five years, but I’ve decided it’s time they come inside.

Only two of these utilitarian stoneware objects is marked, a one-gallon jug from J. and E. Norton Bennington Vermont, made between 1850-1859. A small churn or storage jar from J. D. (J. Dorris) Craven (1827-1895), made in the mid-19th century. The Craven family of potters has lived and worked in the Piedmont area of North Carolina since the 1770s. Of the others pictured here, the first jug on the left and the straight-sided crock on the far right are from the Meyer Pottery (Bexar County Texas, as in the greater San Antonio area), both from the late 19th century. Also pictured are two ovoid shaped jars (one double stamped “2” for the capacity) and a small alkaline-glazed jug that I have not identified as to origin, although all three are likely of Southern origin.

Tuesday, October 19, 2021

Jewelry for Art's Sake

I bought the unsigned silver watch cuff (purchased by the gram/ounce) at a high end coin and jewelry shop. Featuring fish scale inlay turquoise, it was probably made at least 60 years ago at Zuni. Bought a rough slab of jet stone (organic rock created when pieces of woody material are buried, compacted, and then go through organic degradation) at Mama’s Minerals in Old Town Albuquerque. The lapidist there cut a stone 20mm x 30mm for Elgin to convert the cuff to a straight forward bracelet. Few people wear watch cuffs or tips these days, although I do have a few because I love the workmanship on the pieces.

The crude copper cuff I bought in Bryan, Texas, February of 2017. I remember the day well. I was with my sister Joan, in Texas on the last extended visit I made to Texas, when I still had stewardship of the two-story barn home I gifted to one of my other sisters that July. The penny was soldered to the cuff. I harvested the sugilite and coral stones from something sometime here. Elgin made a silver bezel for the stones. My only regret is that the oxidized surface on the cuff got lost in the translation. Small loss given the smashing (fab, gorge) results.

Can’t remember the name of the Santo Domingo (Kewa) Pueblo artist, who along with her husband created the pendant with a spiny oyster base inlayed with jet, mother of pearl, and a jet powder and resin mix.

It was Indian Market, and this expectant mother was selling in the garden courtyard of the Governor’s Palace. Her mom accompanied her that day. Elgin made the concho button and hook for it.

And finally, the spiny oyster stone found at a pawn shop nearby came in an 1980s/90s pendant, set in blah, commercially-produced silver work. Elgin made the bezel and bale. Yumbo jumbo all, y'all!

Tuesday, September 14, 2021

Stepping off the Merry-Go-Round

For awhile there, I guess I thought, “if it needs to be said, then I need to say it”. But the time has to be right. I’ll know because it will come spilling out. Or maybe it’s the place—from a distance, like on paper or in the world we’ve come to know, online. I know that I am an introvert. I would know this without having taken the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) because, well, I know how I feel about things, and I know how things make me feel. I’ve just read that INfJs are the rarest MBTI personality type, making up only 1% to 3% of the U.S. population.

We are compassionate, relying on our strong sense of intuition and emotional understanding. We can be soft-spoken, but this does not mean that we are pushovers. We have deeply held beliefs and an ability to act decisively to get what we want. How many times have I heard, “Harold, why don’t you tell us what you really think.” Chuckle chuckle. Sometimes strong opinions just have to be given voice.

We can form strong, meaningful connections with other people. While we enjoy helping others, we always need time and space to recharge. Unlike extroverts who are energized by situations that require lots of interaction with others, introverts are depleted by these interactions. Typically for me, I just want to get home, close the door and be alone with my thoughts, and do only what I want to to do, which may be absolutely nothing. I had a house guest over the summer—a friend of almost 50 years—who visited three different times in the course of three weeks, a couple of days at a time. At the end of this visit, I was “worn to a nub,” as the expression goes, and resentful. Some part of me—an important part—still hasn’t recovered from these visits.

We are idealists, and we use our abilities to translate this idealism into action. I have to add here that while I haven’t slipped into the world of cynicism, I find it harder and harder to keep my head above water in the seas of meanness and dysfunction that have come to characterize our time. Even though I subscribe online to some of the best sources of writing and news reporting—New York Times, Washington Post, The Atlantic—I struggle to find things that I want to read.

We like to exert control of situations by planning, organizing, and making and acting upon decisions. And I’ll add that as leaders we encourage those who support the work we do to step up, voice their ideas, and take their own leadership roles. And to get credit for what they do.When making decisions, INFJs place a greater emphasis on their emotions rather than objective facts. And while we don’t see the world through rose-colored glasses, we understand that our world is filled with both good and bad, we hope to make it a better place. To borrow a well-used expression, we seek to be part of the solution, not part of the problem.

Push come to shove, when our resources feel depleted, we have to step off the merry-go-round. Over the years I have found this to be true more and more frequently. An article of the December 2017 issue of Smithsonian Magazine explores the famously misquoted words of Greta Garbo regarding alone time. “I never said, ‘I want to be alone,’” she explained, according to a 1955 piece in LIFE magazine. “I only said, ‘I want to be let alone! There is all the difference.”